The Life and Death of Elisabeth, the Queen Consort of Hungary

A short outline – Part Two

Elisabeth of Bavaria (24 December 1837 – 10 September 1898) was the Empress of Austria (1854-1898) by marriage to Emperor Franz Joseph I (18 August 1830 – 21 November 1916) and was the Queen consort of Hungary from 1867 to 1898. She was surrounded by love and worship in Hungary during her lifetime, which increased after her tragic death. We, Hungarians call Elisabeth “Erzsébet”, which was the form she liked to use in her Hungarian conversations and letters. The Queen learnt to speak our language as a native speaker, what is more, she had her fourth child, Marie Valerie taught this language as her mother tongue. It was the language she used when talking to Valerie.

The first part of the article can be read here: The Life of the Legendary Sisi.

Elisabeth with her dog Houseguard (by Rabending, 1866) © Austrian Library, No.: Pf 6639 E 59 3

Elisabeth felt attracted to the Hungarians. She had chosen Hungarian ladies-in-waiting since the early 1860s, who accompanied her to both Vienna and her journeys. The first woman who taught Elisabeth a few Hungarian words was her son, Rudolf’s Hungarian wet nurse. Then later, in Madeira, she learnt from the Hungarian Count Imre Hunyady, who became one of her great admirers. In the Portugal island, Sisi met Imre’s sister, Lili, who was at her age. Lili was the very first Hungarian woman Elisabeth developed a close friendship with. Sisi also had a heartfelt relationship to a Hungarian noblewoman, Ida Ferenczy, which kept for a lifetime. Ida got into the Viennese court under special circumstances in 1864. The Empress had wanted to improve her Hungarian language knowledge and decided to take a Hungarian conversationalist. Only countesses could be her ladies-in-waiting and recommended to her on a list. However, Ida Ferenczy’s name added in different handwriting aroused Elisabeth’s curiosity, and she chose her to meet. Sisi found her likeable even during their very first meeting and took her into her most immediate circle. Ida spoke to Elisabeth about the Hungarians a lot, and her role in the Reconciliation and the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867 was crucial and determining.

Elisabeth and the handsome former rebellious revolutionist, Count Gyula Andrássy met in Vienna for the first time in January 1866, when the Count was a member of the Hungarian parliamentary delegation, which invited the Empress to Hungary. Elisabeth was wearing a richly decorated Hungarian dress. She replied to the invitation in Hungarian, which amazed every delegate even if she still had some accent. In January 1866, the Empress travelled to Hungary. Elisabeth developed a lifelong friendship with Count Andrássy, whom Franz Joseph appointed to be the first Prime Minister of Hungary, 1867. Despite the gossips, the relationship between Elisabeth and Andrássy was only friendship and not romantic love.

Count Gyula Andrássy around 1885 © Austrian Library, No.: Kor 414/1

The Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867

On 8th June 1867, Franz Joseph and Elisabeth became crowned King and Queen of Hungary in Matthias Church, Buda Palace. So as the Hungarians could express their gratitude towards Elisabeth for playing the role of the mediator between the Emperor and them in connection with the Reconciliation, they crowned Elisabeth on the very day that Franz Joseph. It was the first time a Hungarian king and his wife were crowned simultaneously. (The second and last time was when Zita was crowned together with Karl IV on 30 December 1916 – after Franz Joseph died on 21 November.) There was another aspect of this gesture: the Hungarians knew how demanding each public appearance was for Elisabeth, that is why they wanted to decrease the numbers of the ceremonies. Following the Hungarian tradition, before the day of the coronation, Elisabeth mended the royal mantle. On the coronation ceremony, the holy Hungarian crown was held above her right shoulder. The coronation mass was composed by Franz Liszt (the famous Hungarian composer).

It must have been before the coronation when Elisabeth let her husband visit her bedroom for the last time. The Empress decided to give birth to another child if the Emperor was willing to make a compromise with the Hungarians. Her decision was a deliberate personal choice and a political negotiation as well: by returning to the marriage and making her husband – who adored her and tried to fulfil almost every desire of “his beloved Sisi” – satisfied, she ensured that Hungary, which she felt an intense emotional alliance with, would gain an equal footing with Austria. The Viennese and the Hungarians called the fourth child, Marie Valerie the Hungarian Princess because she was born in Hungary (22 April 1868) and spent a significant part of her childhood there. (The Viennese called her like that with sharp irony, the Hungarian did so with affection.) Besides, according to Elisabeth’s instruction, the little girl was allowed to speak to her parents only in Hungarian, and she was educated mostly by Hungarian teachers. (Note: Valerie also had, for instance, an English governess until the age of six. Her name was Mary Throckmorton.)

The coronation at the Matthias Church (a photo of the painting) by Eduard von Engerth © Austrian Library, No.: 195.903 - B

The Vigadó Concert Hall: Viennese Balls and Hungarian Parties

At the time of the Hungarian coronation, Sisi was 30 years old, but even later, in her 40s, she seemed to be a beautiful, magnificent, unapproachable and fairy-like queen at all the places she appeared, including weddings, receptions and, of course, balls. The tradition of balls has its roots in the Austro-Hungarian monarchy. The Vigadó Concert Hall (Budapest) opened by a magnificent ball on 15th January 1865. This concert hall provided a venue for both balls and receptions. After the Vigadó Concert Hall had opened, balls followed balls. On the occasion of the coronation, 1867, a ball, so-called Széchenyi-ball was organized. The King and Queen, that is, Franz Joseph and Elisabeth opened the event. At a ball (a formal dance party), for example, "the waltz" (composed by the Imperial court composer, Strauss) was always danced. Waltz is still very popular at each ball in Hungary and Vienna as well. The Empress was fond of the Hungarian culture and also loved Hungarian dance parties, where "Csárdás", which is undoubtedly the most popular and important traditional Hungarian folk dance, was danced. Besides Hungarian music, Sisi also listened to Gypsy music.

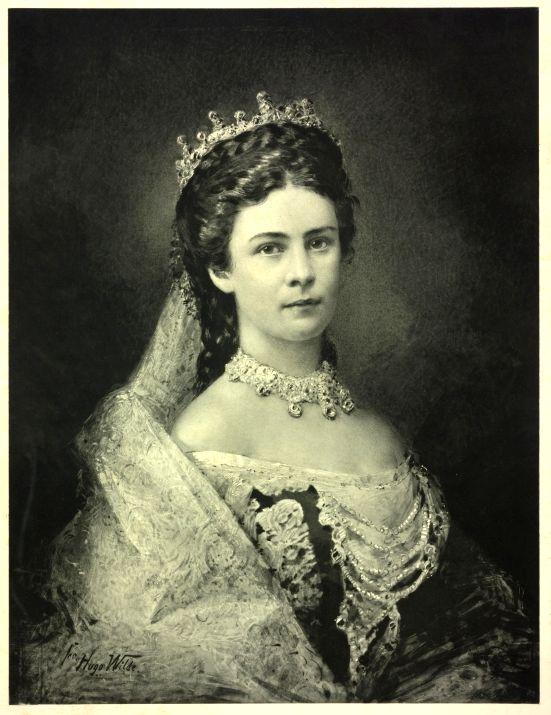

Queen Elisabeth © Austrian Library, No.: III/3/96

The Royal Palace of Gödöllő

On the occasion of the Hungarian Coronation of 1867, the Hungarian state bought the formal Grassalkovich Palace of Gödöllő and provided that as a residence for the royal family knowing that Elisabeth was not fond of Buda Palace, which was the official residence of the royal family, and did not feel herself well either in the two Viennese residences, Hofburg and Schönbrunn Palace. Choosing and buying this palace and its estate was a noble gesture from the Hungarians towards their beloved Queen. The Hungarians also hoped that the royal family would spend a lot of time in Hungary afterwards. In Gödöllő, Franz Joseph and Elisabeth got closer to each other because they could spend time together freely on their common passions: love of nature, horse riding and hunting. Gödöllő Hills had been a hunting ground since the Middle Ages. Sisi was particularly fond of the English style hunts. On the hunts and greyhound races, the top members of the Hungarian aristocracy took part. The Queen was considered to be one of the greatest riders. Gödöllő was Elisabeth’s land. Her laws ruled here, which were unrelated to rank and protocol. Guests were not chosen according to their nobility but (also) according to their riding skills.

Elisabeth spent more than two thousand and six hundred nights in Hungary, which is significant if we think of her travelling passion. She felt a close connection to her Hungarian ladies-in-waiting, who often became her confidence. Countess Maria Festetics was another lady, who is much worth mentioning when talking about the Empress’ Hungarian companions. She escorted her Majesty to nearly all of her travels between (the very end of) 1871 and 1894.

The royal family in the park of the Royal Palace of Gödöllő © Austrian Library, No.: NB 505.988 - B

The Ageing Empress

Perhaps Elisabeth was unaware of the fact that it was also her who made herself become a myth and legend already in her lifetime. Each public appearance was extremely demanding for her as she always wanted to impress representing “the perfect beauty”. She had already become a legend thanks to her beauty during her lifetime. She did not allow any photos taken of her after her early 30s, and soon she refused to seat in front of painters. Furthermore, after the death of her only son, Crown Prince Rudolf in 1889, she wore black dresses most of the time and hardly ever appeared in public, if so, she hid her face behind a fan or/and a veil that is why her old face was unknown by most of her contemporaries as well as nowadays. She left the impression of a young, slender, beautiful and mysterious empress on the history. Hungary was the place, where Elisabeth made her very last public appearance during the celebrations of the Millennium (a period of one thousand years counted from the foundation of the Hungarian state) in 1896.

“Millennium Worship” (a photo of the original) painted by Gyula Benczúr, 1896 © Austrian Library, No.: Pk 353, 148

The Assassination

Empress Elisabeth was assassinated by an Italian anarchist Luigi Lucheni, on 10th September 1898, when she travelled incognito (as most of the times) to Geneva, Switzerland. However, someone from the Hôtel Beau-Rivage, where she stayed, revealed for the press that the Empress was their guest. Lucheni got to know from the daily paper (at least later he said it to the police). Lucheni, like many other people, knew that Elisabeth often refused the aid of the police and the bodyguards. At 1:35 p.m. on Saturday 10th September, Elisabeth and her Hungarian lady-in-waiting, Countess Irma Sztáray left the hotel on the shore of Lake Geneva on foot to catch the steamship Genève for Montreux. They were only a hundred metre far from the harbour when Lucheni was marching towards them. They moved aside but then he raised his right fist and measured a powerful punch to the Empress’ chest, who collapsed hitting her head against the pavement. However, her tightly braided hair soothed the fall. However, her tightly braided hair soothed the fall. Not having felt the stab, the Empress was convinced that the stranger had wanted to take her watch. She collapsed only on the board a few minutes after the departure. Countess Irma Sztáray untied the unconscious Elisabeth's corset, and only then she saw a small triangular scar and dried blood drops over the left breast. It became clear to her that her Majesty was assassinated. The Empress fell into a coma a few minutes to two o’clock, and she passed away at twenty to three. She did not suffer much. According to the medical opinion, Elisabeth could walk towards and board the ship on her own feet not being aware of the stab because the bleeding of the narrow-opened wound had not started immediately and the blood had been seeping slowly through the pericardium. She died as she wished: far from all, she loved, quickly, without suffering. She foretold her death when saying that her soul would leave through a little gap in her heart.

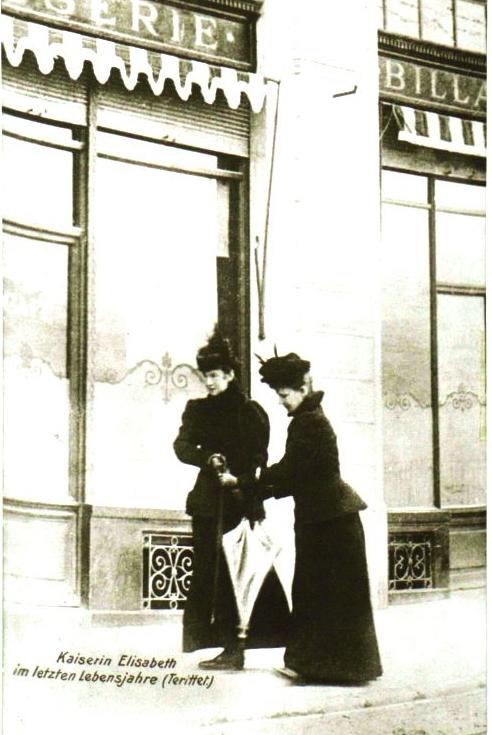

Elisabeth (taller lady, on the left) with Irma Sztáray (on the right). The photo was taken by a paparazzi in Territet a week before her death on 3 September, 1898 © Austrian Library, No.: Pf 6639 E 112/2

Queen Elisabeth Memorial in Buda Palace

After Elisabeth’s death, her conversationalist, Ida Ferenczy and the Queen’s two daughters, Archduchess Gisela and Archduchess Marie Valerie were changing letters a lot. All the three women took part in the establishment of the Queen Elisabeth Memorial in Buda Palace, Hungary. Most of the exhibited relics were donated to the museum by Ida Ferenczy, but Gisela and Marie Valerie also gave several objects which belonged to the Queen, such as the upper part of the dress Elisabeth was wearing when assassinated (this blouse had been in the property of Valerie). The museum opened on 15th January 1908. However, during the Second World War, it was destroyed, and only a few of the exhibited relics survived (such as, fortunately, the dress mentioned above), which are now owned by the Hungarian National Museum. Article recommended: The Portrait of a Queen

Barbara Káli-Rozmis, Researcher and lecturer of Empress Elisabeth of Austria

Elisabeth – photo of the posthumous portrait by Fülöp László, 1899 © Austrian Library, No.: Pf 6639 E 110

Sources and further readings in English:Brigitte Hamann: The Reluctant Empress: Elisabeth of Austria. 1988Egon Caesar Conte Corti: Elizabeth, Empress of Austria, 1935Olivia Lichtscheidl - Michael Wohlfart: Elisabeth. Empress and Queen. 2016Katrin Unterreiner - Verlag Christian Brandstatter. Myth and Truth. 2006

Thank the Austrian Library for the photos.

Cover photos are involved in the article, except picture 1 © Austrian Library, No.: Fid 267798-E

In Memoriam Empress and Queen Elisabeth